08 sep Child of Biafra

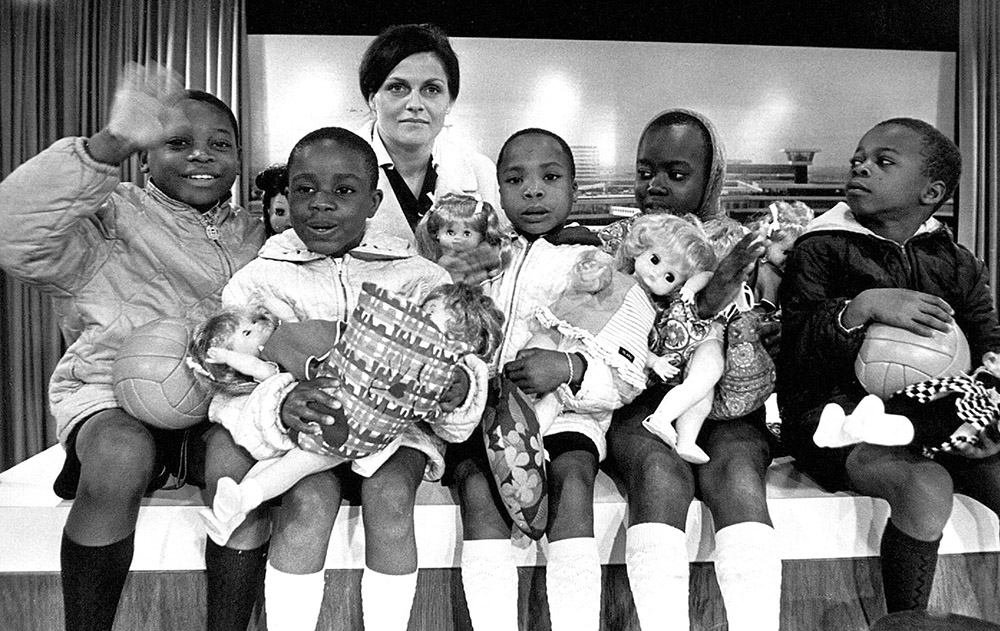

Photo above: Stewardess and nurse Marlies van Schie with Asuquo, leaving for the Netherlands. Photograph from the Van Schie private archive.

In 1968, ten children were airlifted from the war in Biafra to the Netherlands, where they could recuperate.

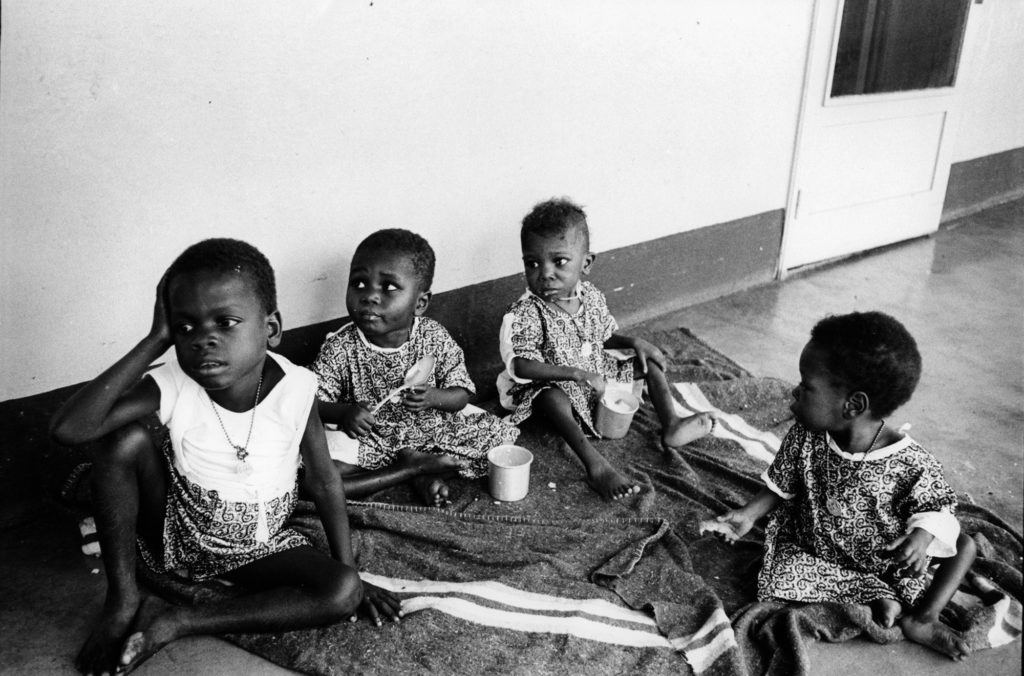

Most of the time they would stare vacantly into space; occasionally they would cry, quietly. In the late 1960s, the world’s attention was gripped by a horrific war whose victims were first and foremost children. I saw them on television, with their stick-like legs and ballooning bellies. They were of my generation, these children of Biafra, Nigeria.

The young colonel Emeka Ojukwu had declared independence for the south east in 1967. The federal army surrounded the area, depriving the population of food, and the weakest died while the cameras watched on. Never before had we seen children used as pawns in a war fought using hunger as a weapon.

It was 15 years ago that I found the photograph of five Biafran children, and I was immediately intrigued. The picture was taken on 7 May 1969 and showed the two boys and three girls cheerfully posing for the camera at Amsterdam’s Schiphol airport, presents in hand, under the watchful eye of their carer.

The caption said they had come to the Netherlands for six months, to recuperate. Their names and ages were also given. The relief organisation Terre des Hommes (TDHIF) was responsible for the children, and although the war in their homeland was not yet over, they had been offered refuge in Gabon, one of the countries that had officially recognised Biafra. The following day, the photograph appeared on the front page of every Dutch national newspaper, and the children also appeared on television.

Despite this, the spokesperson at Terre des Hommes was unable to tell me who these children were or was the brain behind this initiative. Through exhaustive searches of the archives I traced a few of the people involved, but they said they couldn’t recall anything about these events – until, that is, I met Adrie Voorhoeve. She was working at the time at a hospital in the war zone, and it was she who examined the children to assess whether they were well enough to travel to the Netherlands. When we met at her apartment in the Dutch town of Zutphen, she filled me in on the figure behind the project: Abie Nathan (1927-2008), an Israeli pilot and peace activist. ‘Those children were Abie’s showroom models,’ Adrie explained, ‘Not everyone was keen bringing the children to Europe. He pushed it through.’

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Photo above: The first group before their departure from Schiphol. Front row, from left to right: Emmanuel, Margaret, Fidelia, Victoria and Udo Udo. Behind them, their carer Evelien de Jong Winkler

Nathan visited Nigeria several times in 1967. He managed to arrange a plane that he used to fly in cargos of oranges and salami sausages – not the most suitable sort of food for doomed children, but nobody reproached him for that. Nathan had made a name for himself as a peace activist in 1966, when he flew solo from Israel to Egypt because he thought it was about time for peace talks and wanted to help get things started. His mission was unsuccessful, but it made him world-famous.

The Biafran War reminded Nathan of the Second World War, and it was no great leap to compare what was taking place here with the persecution of Jews. In the garden of the hospital where Adrie Voorhoeve worked, Nathan – this distinguished-looking man who served porridge to starving children – addressed the world press: ‘I stand here today as a Jew, as an Israelite, and as a living being. I believe I must do something. It is the duty of all people to come here and lend a hand’, he told a Dutch camera team, ‘We’re able to get to the moon, but we can’t eradicate hunger from the world.’

He had put his finger precisely on the sore point, because people were unwilling to simply stand by and watch so soon after the Second World War. Children collected bottle tops to generate money; adults demonstrated and donated. Nathan’s views were in line with those of a group of Dutch businessmen who had a plan to fly more children over, give them medical treatment, and then fly them back. The men made frequent appearances in the media, to great effect.

In September 1968, the question ‘Can we take in children from Biafra?’ was discussed in the Dutch parliament. The Minister for Justice and Security, Carel Polak, consented to allowing two groups of five children into the country; he was not in a position to endanger relations with the Nigerian government, because Royal Dutch Shell had for some time been drilling for oil in the war zone.

Photo above: The second group. From left to right: Asuquo, Chukwudi, Onuekwuzunma and Joy. Photograph by Daniel Koning

Abie Nathan’s aim was to introduce European children to their Biafran peers, believing it would be a learning experience for all concerned. He was an initiator, not an implementer. He used his charm to win over not just the nursing staff, but also the Pope, Indira Gandhi and John Lennon. He also cajoled the Biafran military leader Emeka Ojukwu (1933-2011) into allowing children to go to the Netherlands. Together, they played on the sentiment that this was not just any war, and that it should not be allowed to simply slip from the world’s gaze. Ojukwu even hired in an Geneva-based advertising company for the purpose, and gave press conferences in the garden of his house in Enugu, close to the warfront.

The Dutch nurse Henriette Liscaljet (1934-2001) was deeply impressed by the exotic figure of Nathan. She selected children, arranged visas and, together with Nathan, brought the first group to the Netherlands. Later, Liscaljet and the second group got stranded on the island of Sao Tomé. By that time Nathan was focusing on another project, the Biafra Christmas Ship. Nonetheless, after weeks of delay, Liscaljet miraculously managed to reach the Netherlands with her group of critically ill children.

Upon their arrival on 13 December 1968, the children were admitted to Princess Irene Children’s Hospital in Arnhem. Two of the boys died, and were buried in the city’s Moscowa cemetery. After three months in the country, 2-year-old Joy was taken in by a family in Uithoorn. The two surviving boys, 18-month-old Chukwudi and 5-year-old Asuquo, stayed together and went to Bio, a rehabilitation centre in Arnhem. They were inseparable, despite going to different foster families every weekend: the younger of the two would stay with the physiotherapist Cock van den Berg and his wife Clara, while the older boy went to stay with Henk Gemser (later the national skating coach) and his wife Annie. Asuquo suffered from severe epilepsy, but Gemser was able to teach and to read and write.

After the war ended in 1970, a heated dispute arose about the fate of the three children. On multiple occasions the Nigerian ambassador told the chair of Terre des Hommes that, ‘These children belong to Nigeria’. None of the foster parents wanted to let the children go. Chukwudi was unable to travel anyways because he still had to undergo operations, and Joy’s carers deflected the demands with a psychological report that questioned who would benefit if she were to return.

Pressure was exerted on Henk and Annie Gemser, with the physician responsible writing in a report that, ‘It cannot be expected of a Dutch couple that they take in such a child.’

The Gemser’s had no choice but to hand over the boy to a carer from Terre des Hommes. She took him to Gabon, from where you travel to Nigeria. In late October 1971 the news came of Asuquo’s death, causes unknown. ‘I have been unable to process this trauma,’ said Henk Gemser in 2007.

The two that remained are now aged around 50 – neither knows their exact age. One of them lives in Amersfoort, the other in Amsterdam. Until recently they were unaware of what lay behind their presence in the Netherlands or what had happened to the others. All they did know was the story of the man named Abie Nathan, to whom they owed their lives. Terre des Hommes was unable to provide details about their past, so information is limited to this: Your parents have died, everybody was dead, and then Abie Nathan came in his aeroplane and saved you.

This article was published in de Volkskrant in oktober 2017. Translation Steve Green.

The war for independence

In May 1967, Emeka Ojukwu declared independence for Nigeria’s Eastern Region, naming it the Republic of Biafra for its coastal bay. His predominantly Christian Igbo community demanded cessation from the federation, which at that point was headed by the Hausa, a predominantly Islamic people. What followed was a blockade that led to the death of an estimated 1 to 3 million victims. On 10 January 1970, Biafra became once again became part of Nigeria.

Goede bedoelingen

Goede bedoelingen, de onvoorziene gevolgen van internationale noodhulp is het gereconstrueerde levensverhaal van tien oorlogskinderen die eind jaren zestig vanuit Biafra naar Nederland zijn gehaald.

Ze waren de mascottes van een gruwelijke oorlog. De kinderen van Biafra. Voor het eerst gingen beelden van uitgemergelde kinderen op televisie de hele wereld over. In 1968, tijdens de eerste grote Nederlandse hulpactie voor hongerend Afrika, kwamen tien van hen aan op Schiphol, om hier medische behandeling te krijgen. Iedereen was het erover eens: dit mogen we niet laten gebeuren! Red je een kind, dan red je de wereld.

Van deze actie resten nu, vijftig jaar later, een paar foto’s in een archief. Voor journaliste Marie Louise Schipper het begin van een lange speurtocht. Wie waren deze kinderen? Wat is er van hen geworden? Twee van hen bleven in Nederland. Zij groeiden apart van elkaar op, bij Hollandse families. De actie Luchtbrug Biafra betekende een ingrijpende wending in hun leven. Hoe kijken zij terug op dit initiatief vol goede bedoelingen?

Wat er met de andere acht was gebeurd, liet zich minder gemakkelijk ontrafelen. Waarom mocht de ernstig zieke Asuquo bijvoorbeeld niet hier blijven? Welk lot wachtte hem en de anderen na terugkeer? Hoe goed waren de intenties van de hulpverleners eigenlijk? Het antwoord op die vragen blijkt even verrassend als onthutsend.

Goede bedoelingen is niet alleen een aangrijpende reconstructie van de eerste grote Nederlandse hulpverleningsactie, het biedt ons ook inzicht in de keerzijde van de politiek van goede bedoelingen.

Deze reconstructie, waaraan ik ruim tien jaar heb gewerkt, werd op 27 oktober 2017 gepubliceerd onder de titel Goede bedoelingen bij uitgeverij Balans.

Bestel het boek hier

Henriëtte van Hoven - Schreuder

Geplaatst op 21:06h, 06 septemberHallo Marie Louise, wat een goed bericht dat je toch dit jaar 2014 het bijzondere werk van ” de kinderen van Biafra ” uit gaat brengen. Alvast mijn hartelijke gelukwensen, en ik hoop spoedig dit, vast hele indrukwekkende werk, van je te lezen.

Heb je enig idee wanneer ’t precies uitkomt,

Met vriendelijke groet, Henriëtte van Hoven – Schreuder.

marielouise

Geplaatst op 21:25h, 06 septemberHa Henriëtte, wat leuk jou hier te treffen! Het boek heet 8 hoofdstukken en ik werk nu, as we speak, aan nummer 6. Nog even te gaan, het is een heel gepuzzel, maar als het zo ver is, hoor je zeker van me. We houden contact! Hartelijke groet, marie louise

Ineke Berentschot

Geplaatst op 21:04h, 04 oktoberha Marie-Louise,

ik was aan het kijken of je boek al uit is gekomen, nee dus, je bent nog aan het werk.

Wat was jouw aanleiding om dit onderwerp te kiezen?

Ken je een van die kinderen?

Of wil je nog nul komma nul erover zeggen?

Hartelijke groet, Ineke

marielouise

Geplaatst op 21:10h, 04 oktoberHai Ineke, Dat was toeval! De Biafra-oorlog was een begrip in mijn jeugd en tien jaar geleden vroeg ik mij af hoe het met die kinderen zou zijn, toen veertigers. Ik zoek en ik vond en nu ligt er een enorme puzzel die bijna is gelegd, maar zich moeilijk laat opschrijven. Vandaar dat ik er al een tijdje mee bezig ben. Ik ken inmiddels vier van de tien… Maar als het boek er is, laat ik het je zeker weten! Groetjes, marie louise

Marijke Heuff

Geplaatst op 14:41h, 14 januaribeste Marie Louise

Wat mooi dat je al een uitgever voor je boek hebt gevonden. Mocht je goede foto’s van Biafra en Gabon nodig hebben, dan heb ik een heel album vol. Ben in middels beroepsfotograaf, dus ik sta in voor de kwaliteit. Uiteraard gratis te publiceren. Ook zit ik nog met een stapel kindertekeningen uit die tijd. Sprak toevallig gister met Jelle Vleer over mijn album waar deze onder te brengen voordat ik “omval”

Hoor ik van je?

hartelijke groet,

Marijke

marielouise

Geplaatst op 15:59h, 14 januariWat leuk Marijke! Heb je bericht in goede orde ontvangen en je ook inmiddels gesproken. We houden contact!

Hartelijke groet, marie louise

joke boon

Geplaatst op 08:58h, 25 januariik verheug me zeer op je boek Kind van Biafra!

marielouise

Geplaatst op 09:02h, 25 januariIk ook Joke! Dat is lief van je!

Hennie van Losenoord -Onck

Geplaatst op 21:37h, 09 oktoberHallo MarieLouise

Wij hebben ook nog contact gehad over die kindjes ,die toen in het Ziekenhuis in Arnhem lagen,waar ik toen werkte.

Zou graag het boek willen bestellen als het klaar is.

Hartelijke dank al vast.

Hennie van Losenoord -Onck

marielouise

Geplaatst op 07:42h, 10 oktoberHallo Hennie, Wat leuk van je te horen! De planning is dat het boek in mei 2017 verschijnt, dan is het vijftig jaar geleden dat de oorlog uitbrak. IK zal je op de hoogte houden! Hartelijke groeten, Marie Louise

Eric

Geplaatst op 12:14h, 11 januariHello Marie Louise, good afternoon, my name is Eric from Nigeria, and I live in The Netherlands.

I know the situation. So happy to see you are following the children from Biafra and writing a book about it. If I can be of any help please contact me on this page.

Jeroen Boland

Geplaatst op 14:52h, 26 januariMarieLouise, n heel bijzonder project. En voor velen, jeugdherinnering, de eerste überhaupt van Afrika of de wijde wereld,

Mocht je een recensent of (fragment)proeflezer zoeken; ik hou me, als (afgekickte) afrofiel, aanbevolen. Succes & sterkte –

Vrnd grt Jeroen Velp

marielouise

Geplaatst op 18:07h, 26 januariDankjewel Jeroen, ik hou het in gedachten!

ank koster

Geplaatst op 20:05h, 27 oktoberMooi de foto op de boot. roept veel herinneringen op. Zag ook een artikel op de pagina van Nieuwsuur.

tot volgende week, ik kijk ernaar uit, Ank

marielouise

Geplaatst op 09:57h, 28 oktoberDankjewel Ank!

Elly Hendriks-Jehee

Geplaatst op 16:50h, 29 oktoberGefeliciteerd met het boek, ik kocht en las het meteen,ternagedachtenis van mijn zusje Marianne,wij hebben in die tijd zo met haar meegeleefd,

Vr. Groet ,Elly H.

Willem Molemaker

Geplaatst op 21:42h, 05 decemberIk herinner mij dat ik op de middelbare school uitverkoren werd om namens mijn klas te demonstreren in Den Haag tegen deze burgeroorlog en de hongersnood. Op de terugweg hadden we pauze in een wegrestaurant, waar we uitgebreid te eten en te drinken kregen. Dat vind ik toen al vreemd. Later, toen ik in Nigeria werkte, begreep ik iets van de complexiteit van de situatie. In de Nigeriaanse literatuur is deze geschiedenis nog lang niet voorbij.

marielouise

Geplaatst op 09:40h, 06 decemberWat interessant, meneer Molemaker. Wat voor een werk deed u in Nigeria?

Willem

Geplaatst op 21:34h, 04 juniIk was leraar op een middelbare school in Plateau State, rond 1980.

Ik zie nu pas jouw vraag.

marielouise

Geplaatst op 21:56h, 06 juniDankuwel!